In the 1950s, a music-loving Australian scientist named David Warren revolutionized aviation safety with an idea born from curiosity: the black box flight recorder. This now-ubiquitous device, which records critical flight data and cockpit conversations, has saved countless lives by helping investigators understand and prevent plane crashes. Here’s the story of Warren’s groundbreaking invention and its global impact.

A Spark of Inspiration

David Warren, a researcher at the Aeronautical Research Laboratories (ARL) in Melbourne, was investigating the mysterious crashes of the world’s first commercial jet, the de Havilland Comet, in the mid-1950s. Frustrated by the lack of clues, Warren wondered: what if a device could record what happened inside an aircraft just before a crash?

His inspiration came from an unlikely source—a miniature tape recorder he’d seen at a trade show, designed for personal music recording. Warren envisioned a similar device installed on every plane, continuously capturing flight details and recoverable after an incident. This spark of creativity led to the concept of the black box.

Overcoming Resistance

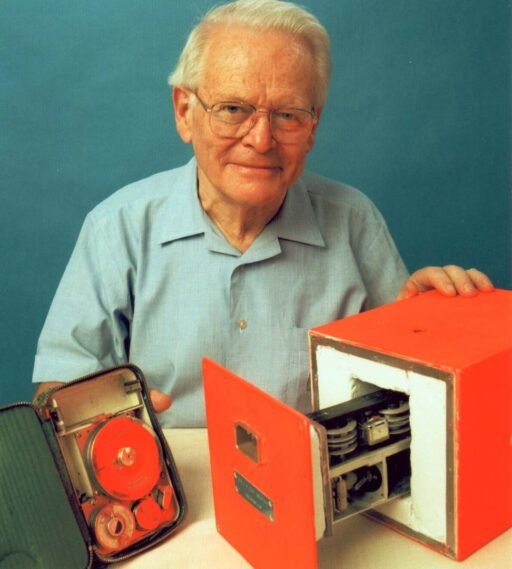

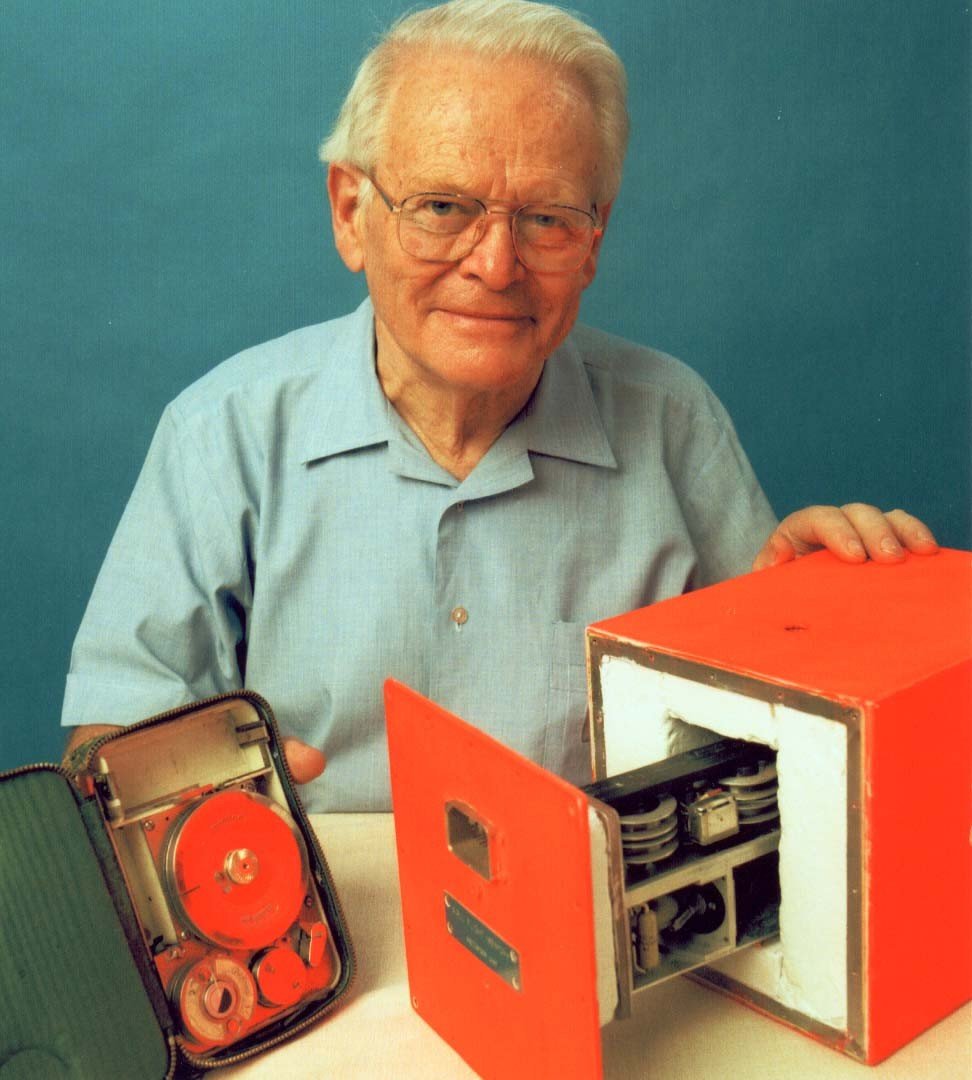

Like many visionary ideas, Warren’s faced skepticism. In Australia, his proposal struggled to gain traction. He published an international report outlining the concept, but it garnered little interest. Drawing on his early experience as a teacher, Warren believed in “show, don’t tell.” On his own time, he built a prototype—the world’s first flight recorder, capable of storing four hours of cockpit conversations and instrument readings.

Despite its potential, authorities remained uninterested. The breakthrough came in 1958 during an informal visit to ARL by Sir Robert Hardingham, a former British Air Vice-Marshal. Over lunch, Warren demonstrated his “unofficial project.” Hardingham saw its value immediately, and soon, Warren and his black box were on a plane to England.

A Global Breakthrough

In the UK, the response was enthusiastic. The Ministry of Aviation suggested that flight recorders could soon become mandatory for instrument data. Warren’s device, nicknamed the “Red Egg” due to its bright, crash-resistant casing, was also showcased successfully in Canada. However, U.S. authorities, invited by the Australian embassy, declined to view it.

Back in Australia, progress was slow. Plans for local production faltered due to lack of support, allowing international companies to take the lead in developing and marketing flight recorders. It wasn’t until 1960, after a Fokker Friendship crash in Mackay, Queensland, that an inquiry judge strongly recommended installing black boxes in all aircraft. Australia became the first country to mandate cockpit voice recorders, cementing Warren’s legacy.

The Black Box: Not So Black

The term “black box” is a bit misleading. Modern flight recorders are painted bright orange or red to make them easier to locate after a crash. Designed to withstand extreme conditions—crushing impacts, intense heat, and deep-sea submersion—they record up to 80 parameters, including speed, altitude, engine temperature, and pilot controls. Today’s solid-state devices use microchips instead of tape, and future versions may even include cockpit video.

Thanks to a British aviation official’s enthusiasm, Warren’s team was invited to the UK to refine the device, encasing it in a fireproof, crash-resistant shell. The “Red Egg” prototype became a commercial success, saving lives by pinpointing crash causes and informing safety improvements.

A Legacy of Safety

David Warren’s black box has become a cornerstone of aviation safety worldwide. By providing critical data after accidents, it helps investigators prevent future incidents, making air travel safer for millions. From a music-inspired idea to a global standard, Warren’s invention proves the power of persistence and innovation.

Want to explore more tech breakthroughs? Dive into our Technology hub for the latest innovations shaping our world!